Nelson J. Wemmer, American Entrepreneur Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Nelson J. Wemmer, American Entrepreneur Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

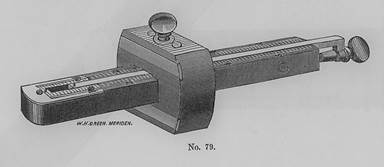

I had never heard the name, Nelson Wemmer, until I began reading American Marking Gauges by Milt Bacheller. There on page 318 was a one page history of Wemmer with a photo of the marking gauge bearing his name. Although the gauge is unremarkable it is somewhat different from the contemporary gauges of his day and that caught my attention. To my knowledge no other Wemmer gauge has been found and is therefore probably unique. It is also probable that he was not a tool maker with this one tool as the only exception. (Photo 1)

Fast forward a year or two from that reading to the September 2010 Martin Donnelly annual auction in Nashua, NH. There, listed in the auction catalog, was this same marking gauge. The gauge was consigned to MJD by that iconic collector and writer, Don Rosebrook. I placed an absentee bid for the item and was the winning bidder. After examining the gauge several questions were raised in my mind. This story is the result of following up on those questions.

Photo 1 The Wemmer marking gauge.

There isn’t much information to be found about the personal life of Nelson J. Wemmer. His life’s story must be gleaned by what we do find in the historical records. The story is comprised of both fact and reasonable conjecture. Nelson Wemmer is one of those men who realized his dream by immigrating to the United States, started several businesses and ultimately becoming successful.

Nilson John Wemmer was born in Denmark about 1802. He immigrated to the US, settled in Philadelphia, married his wife Jane and started a family. Nothing could be found about Nilson’s occupational training. As you check the Philadelphia business directories you see that he was engaged in many varied businesses and his name was then spelled, “Nelson.” From 1837 until 1843 he is listed in the Dry Goods business. The dry goods business is defined as follows, “Textile fabrics, and related articles of trade; as, cloth, shawls, wraps, ready-made garments, blankets, ribbons, thread, yarn, hosiery, millinery, etc., in distinction from hardware, groceries, etc.” This is an Excerpt from ‘A Complete Dictionary of Dry Goods’– By George S. Cole, published in 1892.

After his dry goods career Wemmer spent the year, 1844, as a “Piano Mr” (Manufacturer?). Then from 1845 to 1847 he worked as a Carpet Manufacturer. All during this time he lived and worked at various addresses in Philadelphia. Next, we find Nelson listed as an Artist working at 5 Pear Street which would be his working address for the rest of his life. He is later listed as working at 205-207 Pear and 215 Pear but these numbers are simply a renumbering of the earlier address. His work as an artist was not described although he carried this job description for eight years until 1855. Based on the next phase of his business life I suspect that Wemmer worked as an engraving artist making engraved printing blocks out of boxwood. This is one of my assumptions, however, and I have no evidence to support it.

We ultimately discover Nelson Wemmer as a dealer in boxwood. He remained in this business for the rest of his life. He was very successful in the boxwood business and a major supplier of boxwood to that market. Much of his work was supplying printing blocks for illustrated engravings in the printing industry. This is an exacting business requiring tight tolerances in the boxwood block.

(Photos 2, 3 & 4)

These photos are from one of two engraved printer blocks in the author’s

collection. N. J. Wemmer is stamped on the back.

The front shows a woman carrying a basket on her head.

The boxwood block is 2 3/8” high by 2 9/16” wide by 3/4” thick.

second block in the collection is comprised of six boxwood blocks

joined together and copper faced on the front. It is marked, N. J. Wemmer & Son.

4 3/8” H by 11 7/8” W

In an 1871 publication, ‘American Encyclopedia of Printing,’ we read, “In preparing box-wood (sic) the tree is cut across in slices with a fine saw and the slices after being planed smooth on the surface are cut into square blocks of the required size. The block should be exactly the height of the printing-type in which they are to stand.” N. J. Wemmer of Philadelphia was given as a recommended source of this boxwood in this very publication. To be recommended in this book speaks highly of his reputation in the trade.

Engraved printing blocks were used to print illustrations in all types of publications. The engravings found in the early Stanley catalogs were produced by this method. The engraving on the boxwood is done with gravers. Some of these are the same gravers used in metal engraving. Obviously, the engraving is cut in the negative, like a photo negative. Many of the engravers working during this time became rather famous for their artistry. (Photos 5 & 6)

Photo 5 Engraved illustration of No.79 mortise gauge from an 1859 Stanley catalog.

Photo 6

Ezra Bowman graver patented June 3, 1890.

These types of gravers were used to engrave printing blocks.

We find the name, N. J. Wemmer, in many different publishing endeavors. He made wood blocks for the Government Printing Office of the U. S. Government and his name listed in the financial records. Some of these blocks were later found in the Smithsonian, National Museum of American History. One of the largest customers of the Wemmer firm appears to be the American Sunday-School Union which needed engraved printing blocks to illustrate their books and periodicals. Many of these printing blocks are still extant and housed in a Philadelphia free lending library called, The Library Company of Philadelphia, which is an independent research library concentrating on American society and culture from the 17th through the 19th centuries. It was founded in 1731 by Benjamin Franklin.

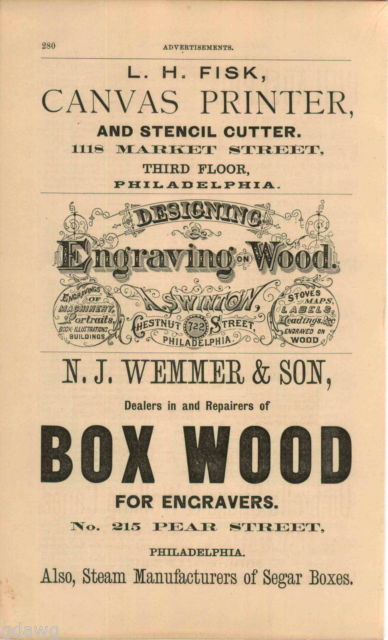

Wemmer was also an inventor. Early in his career, on March 18, 1841, he received patent number 2,011 for his device for “Sharpening Reciprocating Saws.” At that time his name was still spelled, Nilson, on the patent papers. It also shows that although listed in Dry Goods at this time he was involved in woodworking. Later, on February 11, 1868 in collaboration with his son, John, he was awarded patent number 74,263 for an “Improved Branding Machine” for branding cigar and other box panels. We find advertisements by N. J. Wemmer offering Segar (sic) boxes made by steam power and Wemmer’s Segar moulds. (Photos 7 & 8)

Photo 7

Photo 8

Both of these advertisements were published in 1876. The ad on the left was listed in Burley’s United States Centennial Gazetteer and Guide. The ad on the right was found in the 1876 publication, Events of the Century.

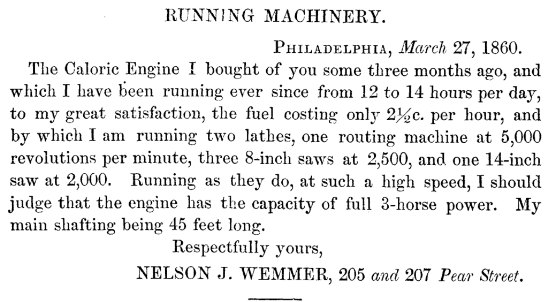

Nelson also pioneered the use of new technology in his production facilities. He installed an Ericsson Caloric (hot air) engine in his factory in early 1860 to run his equipment. (Photo 9) He wrote an endorsement of the engine for it’s maker in 1860. (Photo 10)

Photo 9 Engraving of an Ericsson Hot Air Engine.

Photo 10 Wemmer’s endorsement.

Photo 11 Marking on the head of the gauge.

So, what does all this have to do with a simple marking gauge? This gauge has an 8” boxwood beam with no graduations and a mahogany head with brass thumbscrew. The head of the gauge is stamped, “N. J. Wemmer, Patent, Philada.” (Photo 11) No patent has ever been found to substantiate the “Patent” claim stamped on the head of the gauge. At first glance it looks like a rather common marking gauge. Here are some observations I’ve made that could influence a patent claim. When I received the gauge the scratch point had been reinstalled 90 degrees from it’s original position so that the long portion of the rectangular head could be used against the work. When reinstalled into the proper vertical position there is only about 5/16” of the head to use against the work. Upon close inspection there is a 3/32” diameter hole drilled through the length of the head from side to side. (Photo 12) I believe that would have been the patent feature. What would have been the purpose of this hole? We can never be certain but I have a suggestion. What if this hole received a 3/32” diameter rod? If this rod were mounted in a fixture you could slide the gauge from side to side on the rod to do repetitive work without any further adjustment. By doing this you would be bringing the work to the fixture. I have made a small simple sample fixture that would work in this manner. (Photo 13)

It is obviously less than a stellar idea but many patents were granted for sillier features. Was there ever a patent? We will probably never know but Nelson Wemmer did have patents granted to him before. He worked with small wooden pieces where a faster way to mark would be a benefit. One reason there may not be any U. S. Patent Office information on this gauge could be the disastrous fires suffered by that government agency in the past. The first and worst fire occurred on December 15, 1836. All 10,000 patents and several thousand patent models were destroyed in the blaze. Another fire in 1877 destroyed the west and north wing of the new patent office building again destroying much patent information.

In 1860 William N. Wemmer, one of Nelson’s sons, became part of the firm. He was involved through 1866 but dropped out of the records after that year. Nothing more is known about William except that he died suddenly on November 17, 1889 at 55 years of age. Another son, John P. Wemmer became a partner in the firm in 1867 and the company became, N. J. Wemmer & Son. John P. Wemmer was one of the names on the 1868 patent for the branding machine. Nelson J. Wemmer died on August 17, 1875 leaving his son John as owner of the company. The last listing I could find for Wemmer & Son in McElroy’s Philadelphia Directory was 1876, the year after Nelson’s death. Did the business fold after that year? John P. Wemmer was later listed in Boyd’s 1887-88 Blue Book, a society directory, indicating he was financially well off.

There is an entry in Gopsill’s Philadelphia Business Directory of 1887 naming an Edward V. Wemmer, “Box and Other Wood” dealer, at 611 Sansom Street. Could this be another son or grandson?

Photoengraving became commercially practical in the 1890’s striking a death blow to the wood block engraving industry. Perhaps that finally ended the Wemmer family business. Of course, there were always “Cegar” boxes to be made!

Additional information you might have would be greatly appreciated.

Jim Fox is a member of the Mid-West Tool Collectors Assn. He is a retired church pastor and lives in St. Cloud, FL with his wife, Candy.

Email foxyjim1940@gmail.com